Trust in the Era of Accountability

It’s amazing to watch a conversation evolve. Over the past month I have had some great feedback from physicians, nurses and patients about medical professionalism and the concept of physician accountability. In my last blog post I explored the idea that accountability is not based on finger pointing or blame and need not be feared. Being accountable, I think, has at its core the concept of matching intent to do well with measuring the outcome of that effort. Accountability, then, is actually rather familiar to healthcare providers. It has always been there in the background, but we often don’t analyze its three components well. For discussion here, the three legs of physician accountability are:

- Accountability to our patients

- Accountability to our peers

- Accountability to the healthcare system that we work in

These three integrated and mutually dependent parts are like a three-legged stool. Stability only comes if all three legs are strong. The forces that hold us up must be equal and bidirectional, built into the structure of each leg. Individually one support can flex and bow to a degree, but ultimately all three must be relatively firm for the stool to remain upright.

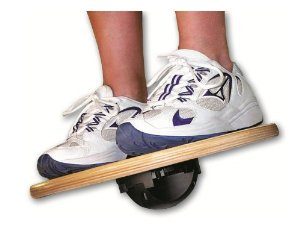

Many physicians commented to me recently that they feel off balance perched on this stool today. In fact, some told me that it does not feel like they are sitting on a stool at all. The platform they are perched on feels more like a Wobble Board where no stabilizing forces or supports exist. Sometimes they are positioned directly over the single point of balance and feel secure, but stability is always very brief. Any outside force causes them to tip.

So how do we build balance back in? How do we ensure that there are three legs equally pushing up against the forces of professional gravity creating a safe place to sit and work? I believe that strength in these supports can be bolstered and rebuilt. Doing so is difficult in troubled times but can be done through the creation of trust.

Balance can be achieved through trust.

Many of us would agree that trust has slowly eroded away in healthcare over the past two decades. Some say that this is just the new world order, but I don’t think we can settle for this as an end state. Recently, I was exposed to and watched an amazing TedX talk by Baroness Onora O’Neill, the esteemed Cambridge philosopher and Chair of England’s Equity and Human Rights Commission. Her analysis of trust has caused me to think about its generation and how this influences our professional relationships. In her lecture Baroness O’Neill states that trust cannot simply be built. It must be earned. Offering up opportunities to trust one another is not just the responsibility of physicians but also of the two other partners we work closely with in healthcare: our patients and the healthcare system.

If trust is currently lacking, how to we earn it?

We do so by being trustworthy.

There is an important difference between the trust and trustworthiness. Baroness O’Neill’s thought is that we as humans assess trustworthiness constantly and on three qualities or traits. These are:

- Honesty

- Integrity

- Reliability

Trust is actually earned over time as we interact with other people, and this is accomplished by fairly consistent displays of the above three traits. Trustworthiness is naturally evaluated by each of us and can be improved with every interaction. Over time, constant exposure to the principles of trustworthiness mends weaknesses in the integrity of the legs on our three legged stool.

What if our partners don’t want to participate?

There has been a change in the trust balance when dealing with our patients and their concerns over the past few years. In the past patients trusted us simply because we possessed a body of knowledge and insight that they did not. In turn, we hoped that they would return this trust by following our advice because they sought it out and found it valuable. There was an unwritten social contract in the doctor/patient relationship, and there still is. But this traditional trust relationship is much less explicit these days. Patients have exposure to hundreds of opinions and unlimited access to information on the Internet. They are much more able to make informed choices as to how they treat and care for themselves without our expertise. Bidirectional trust is now based on a shared relationship and the insight we can offer in interpreting all of their information through the lens of experience and previous exposure to similar patients and problems. As we adapt to this new reality, if we adapt to it, our accountability changes. It becomes more equal. This pillar is the easiest to keep strong because we understand our patient relationship best and practice to perfect it many times each day.

The second leg of accountability is that of peer to peer. Doctors have had trust and assessments of trustworthiness built into our learning from our very first days in medical school. We take advice often uncritically from our colleagues on how to best care for some of our most challenging medical dilemmas. For the most part we trust their guidance. Yet there is variability in trust based on previous experience and individual interactions with our colleagues. I may wait longer for my patient to see Dr. Jones because I trust her judgement more, where Dr. Smith may well have the same level of competence but is not seen with the same degree of reliability or integrity. I have witnessed a divide in our collective trust over the past few years. Some of this is because of system barriers to maintaining a strong medical community of practice (increasing degrees of sub-specialization, siloed locations of practice where hospital and community physicians rarely mix,

The second leg of accountability is that of peer to peer. Doctors have had trust and assessments of trustworthiness built into our learning from our very first days in medical school. We take advice often uncritically from our colleagues on how to best care for some of our most challenging medical dilemmas. For the most part we trust their guidance. Yet there is variability in trust based on previous experience and individual interactions with our colleagues. I may wait longer for my patient to see Dr. Jones because I trust her judgement more, where Dr. Smith may well have the same level of competence but is not seen with the same degree of reliability or integrity. I have witnessed a divide in our collective trust over the past few years. Some of this is because of system barriers to maintaining a strong medical community of practice (increasing degrees of sub-specialization, siloed locations of practice where hospital and community physicians rarely mix,  fewer personal connections with our peers), some is related to demands on our time time (no bandwidth to follow up about a patient, an increasing demand for service volume) and some is about a changing professional mix in our work environments. With effort, though, trustworthiness can be enhanced between peers in this difficult time. Our relationships can be nurtured with dialogue, direct and honest communication, and by working side by side on challenging healthcare issues. Again, to build better connections we need to increase our trustworthiness. We should treat all of our colleagues the way we treat our friends. We must support a diversity of ideas and multiple opinions on how to solve a collective problem. This will strengthen the second leg of the stool. In doing so, we are being accountable.

fewer personal connections with our peers), some is related to demands on our time time (no bandwidth to follow up about a patient, an increasing demand for service volume) and some is about a changing professional mix in our work environments. With effort, though, trustworthiness can be enhanced between peers in this difficult time. Our relationships can be nurtured with dialogue, direct and honest communication, and by working side by side on challenging healthcare issues. Again, to build better connections we need to increase our trustworthiness. We should treat all of our colleagues the way we treat our friends. We must support a diversity of ideas and multiple opinions on how to solve a collective problem. This will strengthen the second leg of the stool. In doing so, we are being accountable.

A very important third leg of accountability comes from our intersection with the larger health care system. This includes the structures that surround our work (hospitals, LHINs, community agencies) and the government that funds it most of it (various Ministries and their leaders, both elected and bureaucratic). There has been a huge erosion of the strength of this wooden stool leg recently. Some would even go so far as to say that it has rotted completely. If we agree that the integrity of the wood itself is poor, then it behooves us to find ways to build in strength and resilience. Trustworthiness is hard to assess when you fear that at any time the three tenets of honesty, integrity and reliability are missing. Right now this leg needs external bracing: building up the trustworthiness of both sides of the relationship. Both providers and system planners must strive for ways to show that each is being honest, acting with integrity and exhibiting reliable competency. This will be hard work, especially when our agendas are not the same. And it will not happen overnight or all at once. Trustworthiness is built up with constant exposure to work done in good faith. It involves transparency, patience, careful observation, examination of failures and celebration of success. The relationship does not need to be perfect for trustworthiness to be shown, and we should be careful not to read more into each other’s motivations and intentions than is needed. But the approach does need to be consistent. To succeed at earning trust both doctor and the health system must view each other with open minds and be ready for gestures of cooperation that come with change so that they are not missed when they occur. Eventually a fractured unstable stool leg will be replaced with a stronger one made of new hardwood. It heals. This wood will not be without its knots, but knots don’t necessarily weaken the core of the wood. It remains strong despite its imperfections and is much more interesting to look at. With earned trust, bilateral accountability is easier to maintain.

Professional accountability is balanced and well supported on a three-legged stool when all three legs are intact and strong.

Patients, our peers and the healthcare system form the structure of these three legs and pressure is exerted bidirectionally through each of them daily. Inherent strength and stability of the stool comes from building trust in our partnerships, through consistent displays of trustworthiness as a brace for each leg. Our challenge, and that of our patients and the government during periods of critical change, is to create processes that encourage honesty, integrity and reliability and bolster them when they occur. Over time, less and less effort will be required to find balance, and eventually there will be comfort felt in just sitting, knowing that we won’t fall over.

6 Replies to “Trust in the Era of Accountability”

Great article Dr. Larsen perhaps we could leverage some Ehealth tools to provide online venues for physicians to more effectively and seamlessly connect with their peers! Some of the tools were showcased at the e health conference.

Thanks for the read Neha, and for commenting!

Yes, there are tools for docs and nurses to use in improved communication to build trust. What is often missing is the change management process that puts them into their everyday workflow!

Lets explore more at eHealth this year!!

Darren

Nicely said.

I wonder if one more process should be added: responsibility. The only way in my mind to be completely accountable, is to be responsible for good and bad outcomes, and to be responsible to improve if needed.

As a medical student, I may not be accountable, simply because I am not allowed to be. My staff physician is responsible to the patient, and thus the accountability lies on them. I definitely feel responsible, and maybe even somewhat accountable, but without being empowered to be able to make major changes (the final decision maker), I can never truly be accountable… that is until I graduate… yikes!

Will…. thanks a lot for that perspective.

I would argue that you are accountable to all three legs of the stool, just in different ways! Accountability does not mean that “the buck stops here” in my opinion. It is part of the structure, process and pattern of every interaction you have with your patients, your peers and the system (which as a student is perhaps more educational than delivery) even as a student.

And you will be an MD in days…. so welcome to this larger exposure and conversation!!

Thanks a lot for commenting!

Great article. As for embedding in everyday workflow…here may be some additional ideas (using one of many change models). Leadership in Health Services Vol. 27 No. 4, 2014 pp. 330-342. ” Embedding physician leadership development withing health organizations.”

Thanks a lot John! Always appreciate your insight and comments! I will look that article up.

Darren